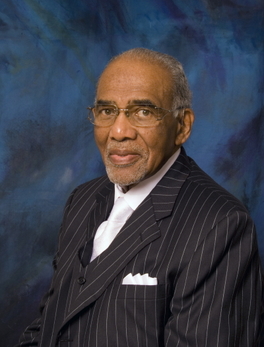

The Rev. Dr. Samuel B. McKinney

The Rev. Dr. Samuel B. McKinney Wikipedia pinpoints the beginnings of Political Correctness – at least, under that banner – as sometime in the 1990s. But it has been with us in some form or other, spoken or unspoken, ever since the first time some wimp got it in his head to compromise justifiable self-expression for fear of being (Hea'en forfend!) objectionable. In the arts, few things are so headache-inducing to the creator or re-creator as an earnest attempt at communication that is compromised or scuttled by someone's oversensitive "I'm offended" button.

I was raised in an extremely open-minded and liberal environment; prejudice was non-existent under our roof (except, as we'd say, "against prejudiced people"). In the era in which I grew up, a comic like Don Rickles would explode prejudices by calling forth epithets and stereotypes during his act, in an effort to show their very ridiculousness and render them easier to laugh away. (We had friends who knew Rickles personally, and vouched for his warmth and humanity offstage.) When Blazing Saddles came out in 1974, my parents returned from the theater still laughing at the bombshell Mel Brooks had dropped, and regaled me with some of the film's over-the-top gags that transpired as Sheriff Bart gradually won over the initially racist population of Rock Ridge. What better way to show the imbecility and limitations of the townsfolk than by having them use language (yes, including the "N" word) that revealed them as the ignoranti they were? It made their education and eventual acceptance of Bart and his friends a tastier reward; an all-out comedy Saddles may be, but few movies have ever attacked prejudice so vehemently and made so potent a statement about it in spite of a putatively fluffy exterior.

It has been opined by many sages that Blazing Saddles could likely not be made today, unless the PC Police were permitted a thorough rewrite of the script to leech out that which today's lily-livered audiences might find repellent. (We could always subject it to the same unfortunate cleansing that befell Huckleberry Finn some years ago; a new edition of Mark Twain's classic about the titular hero's moral education was ridiculously maimed by the removal of every iteration of you-know-what.)

My intolerance for PC surfaced early on. My family were major theater-lovers, and we enjoyed attending productions at the Mark Taper Forum of the Los Angeles Music Center. When I was in my mid-teens, there was a staging of Sean O'Casey's play Juno and the Paycock in which the three principal characters were played by a trio of (to say the least) experts: Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau and Maureen Stapleton. Sadly, this festival of superb drama was dulled somewhat by a series of letters to the Los Angeles Times complaining that the cast only contained one actor of Irish heritage, in a supporting role. In an effort to blow off a little steam, I wrote the following to the Times which ended up being my first-ever Letter to the Editor deemed fit to print:

I am most distressed by the artistic management of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In a recent all-Messiaen concert, the only French performer was the composer's wife, pianist Yvonne Loriod. But the orchestra, soprano soloist and conductor were, respectively, an American orchestra, a British soprano and a Vienna-trained Indian. [The last two references were to Felicity Palmer and Zubin Mehta.]

There, I've said it. I've read it over. And had a good laugh, due to its incongruousness, short-sightedness and stupidity – the same qualities (or faults) that have permeated many of the letters you have printed in recent weeks, specifically those dealing with the casting of Chico and the Man and Juno and the Paycock. [Chico and the Man was a TV sitcom that also aroused ire, for casting a Puerto Rican actor in the role of a Chicano.] What these writers have overlooked in their blind ignorance is the primary artistic esthetic: the work of a creative individual presented to an audience for a (hopefully) joyous experience in communication. But these self-righteous ones only regard these vehicles as opportunities for unleashing their age-old complaints about their offended race, nationality or religion.

If we are to cater to this kind of half-baked morality, then let our U.S. orchestras play nothing but the works of Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber and Leonard Bernstein.

A little rough in the syntax department, but I am still delighted to have put forth a sentiment that I still espouse roughly forty-five years later.

I've had to deal with the PC issue a few times in my professional life (not as many as some of my colleagues, thankfully). In every instance I've been caught off-guard by it, but at least in one case – the last of the three I'll chronicle – there was a delicious helping of vindication.

Many years ago I was conducting a student orchestra at what was essentially a summer music camp. One of the pieces I gave the students was a section from Aram Khachaturian's Gayane ballet. Now, as anyone even remotely familiar with Khachaturian's music knows, one of his most oft-used rhythms is:

1-2-3-1-2-3-1-2, 1-2-3-1-2-3-1-2

– or, put another way:

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8

It's a kicky little rhythm that is undoubtedly a mainstay in the folk music of Khachaturian's native Armenia. It also happens to be a rhythm that one encounters in Jewish folk and popular music; you can hear it in the offerings of klezmer bands, at Jewish celebrations of coming-of-age or nuptials...and I can think of at least one usage of it in the score to Fiddler on the Roof. At one point in our rehearsals for the Khachaturian, the low strings had this rhythm in their parts but weren't emphasizing the accents quite boldly enough. By way of explanation, and speaking purely factually and with no snideness or sarcasm, I said, "Can you make it a little more Jewish?" Somehow, it worked; the young musicians got the point and the passage was played to my satisfaction. (I might also add at this point that my forbears on my father's side were Russian Jews.)

Imagine my surprise when I arrived on campus the next morning and was requested to step into the camp director's office. In the most delicate of terms, I was told that I had offended a Jewish student at the rehearsal the day before, and I was asked for a description of what had transpired. Fortunately, the explanation was all it took for the director to understand that nothing in the least bit damaging had been said, and he assured me that he'd call the student's parents forthwith and put any ill will to rest. (As I was engaged for many subsequent summers, I can only assume that I was not viewed as a threat to the students' delicate psyches.) It was gratifying in the extreme to tell this story to family and friends and get virtually the same reaction from all: "Somebody actually thought you were saying something prejudiced?!?"

A few years later, I was conducting another student orchestra, at a high school that prided itself on its progressive attitudes towards diversity. While admirable in theory, their take on the subject was somewhat different from my own; I would sum up their stance as, "We won't call attention to any ethnic, political or religious aspects of our student population, for fear of making those of other ethnicities, political beliefs or religions feel uncomfortable, marginalized, or excluded." That meant, among other things, that some students' wishes to put Christmas decorations in the cafeteria were quashed. Why not, felt I and some of my faculty colleagues, have students of other religions and ethnic backgrounds put up some of their holiday decorations, too? (Imagine what an attractive and festive display might have been the result!) No, came down the edict, better not to celebrate anything than run the risk of seeing some trends emphasized over others, etc., etc. (How do you say "Bah, humbug!" in Hebrew or Swahili?)

In an attempt to expose the orchestra to the most diverse (!) spectrum of music, I programmed works spanning from pre-Baroque to the late 20th century. Not wishing to bypass the avant-garde altogether, I scheduled a marvelous piece by Gavin Bryars entitled Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet for pre-recorded tape and ensemble (the scoring is flexible, i.e., the piece can be performed by anything from a few instruments and/or voices to a hundred-piece symphony orchestra with chorus). The pre-recorded tape consists of a sung phrase which is repeated as many times as needed (the length of each performance is variable), and at each repetition the conductor can cue in or cut off different "live" musicians, all of whose parts complement the singer on tape. It seemed a fun challenge for the young musicians, certainly outside the realm of playing something in a continuous, steady 4/4.

The voice on the tape was that of a homeless man in England, one of several persons interviewed for a documentary film on poverty, on which Bryars had been working as sound engineer. To quote Mr. Bryars:

In the course of being filmed, some people broke into drunken song – sometimes bits of opera, sometimes sentimental ballads – and one, who did not drink, sang a religious song, Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet... [The accompaniment I composed] respected the homeless man's nobility and simple faith. Although he died before he could hear what I had done with his singing, the piece remains as an eloquent, but understated testimony to his spirit and optimism.

To me, the work is primarily about music – about the timbre of the voice and Mr. Bryars' skill in coming up with so lovely an accompaniment for it. Second is the implicit program, the man's "spirit and optimism". But I do not think of this as a religious work; this is no cantata or oratorio aria, but a quietly moving testament to the composer's having been so stirred. Had the man sung a setting of a Shakespeare or Whitman verse that spoke of fortitude in the face of adversity without mentioning Jesus Christ, it would have just as stirring.

Imagine my surprise when, after describing the work at the Arts Department meeting shortly before the performance, there were some red flags about the piece – not as music, mind you, but the fear of how non-Christians might be offended by the "sacred" text. I managed to plead fairly eloquently on the piece's behalf, and eventually a compromise was reached: we could perform it, but I was to address the audience beforehand to stress that the point of the piece (and, by implication, of our performance) was its musical merits; I all but admonished the audience to ignore the words (which, I told myself with an internal grin, would then be impossible for them to do; if you tell someone, "Don't think about pink elephants!", what's the one thing about which they will surely think?). Pace, alarmists: the piece ended up being the most talked-about work we performed all year, all of the feedback positive.

But my single favorite PC story comes from my days as the Seattle Symphony's Associate Conductor. I love the orchestra, and have a treasure trove of wonderful memories associated with them. This is not to say that there wasn't occasional abrasion, as there is in any relationship of long standing.

In the fall of 1998, when Benaroya Hall was in its first few months of operation, the Symphony offered as varied a series of concerts and events as it could – classical, pop, jazz, film music – in order to attract the most diverse (there's that word again) audiences possible. One of these programs featured Gladys Knight doing an hour or so of her songs with the orchestra, for which she brought her own conductor; as frequently happened when a guest artist had a generous half-a-concert's worth of material, a "short first half" would be presented featuring the Seattle Symphony on its own. I was asked to conduct this first half, and then-Music Director Gerard Schwarz suggested "something American – upbeat, with great tunes – something like Copland's Rodeo or Bernstein's Symphonic Dances from 'West Side Story'." While pondering repertoire choices, I thought of a piece I had known from recordings since I was a small boy: Spirituals by Morton Gould. When I bounced this off of Mr. Schwarz, he said, "Perfect! Do it!" And so it was scheduled.

The third of Spirituals' five movements is effectively the work's scherzo, a charming miniature that Gould called A Little Bit of Sin. It uses a tune widely known as Short'nin' Bread, which you may not know from the title but would likely recognize due to its being used in everything from cartoons to commercials. The rehearsal for it, and the other movements, went well and the orchestra, naturally, played superbly.

Imagine my surprise when two or three members of the orchestra cornered me after the rehearsal, to express their displeasure at the Little Bit of Sin movement. "It's a slap in the face to African-Americans!" they said. "It perpetuates the stereotype of Black servants in the kitchen making pancakes!" I tried to offer some perspective: that this was a work in which a Jewish-American composer was paying homage to a culture other than his own, honoring their music with his composer's expertise – not unlike what the Australian-born Percy Grainger had done with American, Scandinavian and English folksongs in his compositions, or what Copland had done with Mexican themes in his El Salón México. My arguments fell on deaf ears; not only did they resent the programming of the piece, but their deep-seated beliefs led them to go to management to get permission to leave the stage and not play it.

Given my own beliefs, and what I thought the piece was, and what I didn't think it was, I was amazed.

The performance went on (sans the nay-players), and was enthusiastically cheered by a packed Benaroya audience.

As soon as the Gould was finished and I had taken my final bow, I snaked my way through Benaroya to get to the lobby; a friend had asked for a ticket, and we had arranged to meet at intermission if he had indeed made the concert. In the course of scanning the crowd for him, I saw, standing across the lobby, the Reverend Dr. Samuel B. McKinney (1926-2018).

For those of you unfamiliar with the name, I can only skim the surface of Dr. McKinney's extraordinary life. Dr. McKinney's accomplishments included his longtime (1958-98) pastorship at Seattle's Mount Zion Baptist Church. Dr. McKinney had originally intended to become a civil rights attorney, and even though the ministry claimed him, he remained a major figure in the civil rights movement; he marched with his old friend Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, and in Washington D.C., in the early 1960s, after having arranged for Dr. King's only Seattle visit for a series of speeches and meetings in 1961. Dr. McKinney was also an outspoken opponent of apartheid rule in South Africa; his participation in protests against it earned him at least one arrest.

About two or three years before the evening in question, I had had the pleasure of working with Dr. McKinney: he was the guest soloist at a Seattle Symphony concert in which he narrated Copland's Lincoln Portrait. In advance of his first rehearsal with the orchestra, I met him at his church to play the orchestra part on the piano so that he could practice the pacing of his recitations. His bass-baritone speaking voice, which one could only call powerful and mellifluous, was perfect for Copland's score.

That same powerful voice erupted from his throat when he caught sight of me across the lobby. "Adam!" he called, and made a gesture with his arm that as much as said, "Get over here!" (Dr. McKinney's physical presence was as formidable as his voice; he stood well over six feet, and his eyes blazed with intensity.) The phrase "moment of truth" must have crossed my mind as I approached him.

"Adam!" He beamed when I reached him, and gave me a robust embrace. "Thank you so much for playing that Morton Gould piece! I LOVED it! I heard tunes in there I hadn't heard since my grandmother sang them to me when I was a kid! Is it recorded? Can I get it on CD?" I was delighted to answer in the affirmative...and even more delighted at his response to a piece I also loved.

When I went backstage again, I called some of my friends in the orchestra over. "Will you please help me spread the word as to who just thanked us for playing the Gould?"

There's that marvelous scene in Woody Allen's Annie Hall in which a pompous blowhard is dressed down by Marshall McLuhan, the very person whose theories he has been mangling. Woody looks into the camera and says, wistfully, "Boy, if life were only like this..."

Sometimes it is.

I was raised in an extremely open-minded and liberal environment; prejudice was non-existent under our roof (except, as we'd say, "against prejudiced people"). In the era in which I grew up, a comic like Don Rickles would explode prejudices by calling forth epithets and stereotypes during his act, in an effort to show their very ridiculousness and render them easier to laugh away. (We had friends who knew Rickles personally, and vouched for his warmth and humanity offstage.) When Blazing Saddles came out in 1974, my parents returned from the theater still laughing at the bombshell Mel Brooks had dropped, and regaled me with some of the film's over-the-top gags that transpired as Sheriff Bart gradually won over the initially racist population of Rock Ridge. What better way to show the imbecility and limitations of the townsfolk than by having them use language (yes, including the "N" word) that revealed them as the ignoranti they were? It made their education and eventual acceptance of Bart and his friends a tastier reward; an all-out comedy Saddles may be, but few movies have ever attacked prejudice so vehemently and made so potent a statement about it in spite of a putatively fluffy exterior.

It has been opined by many sages that Blazing Saddles could likely not be made today, unless the PC Police were permitted a thorough rewrite of the script to leech out that which today's lily-livered audiences might find repellent. (We could always subject it to the same unfortunate cleansing that befell Huckleberry Finn some years ago; a new edition of Mark Twain's classic about the titular hero's moral education was ridiculously maimed by the removal of every iteration of you-know-what.)

My intolerance for PC surfaced early on. My family were major theater-lovers, and we enjoyed attending productions at the Mark Taper Forum of the Los Angeles Music Center. When I was in my mid-teens, there was a staging of Sean O'Casey's play Juno and the Paycock in which the three principal characters were played by a trio of (to say the least) experts: Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau and Maureen Stapleton. Sadly, this festival of superb drama was dulled somewhat by a series of letters to the Los Angeles Times complaining that the cast only contained one actor of Irish heritage, in a supporting role. In an effort to blow off a little steam, I wrote the following to the Times which ended up being my first-ever Letter to the Editor deemed fit to print:

I am most distressed by the artistic management of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In a recent all-Messiaen concert, the only French performer was the composer's wife, pianist Yvonne Loriod. But the orchestra, soprano soloist and conductor were, respectively, an American orchestra, a British soprano and a Vienna-trained Indian. [The last two references were to Felicity Palmer and Zubin Mehta.]

There, I've said it. I've read it over. And had a good laugh, due to its incongruousness, short-sightedness and stupidity – the same qualities (or faults) that have permeated many of the letters you have printed in recent weeks, specifically those dealing with the casting of Chico and the Man and Juno and the Paycock. [Chico and the Man was a TV sitcom that also aroused ire, for casting a Puerto Rican actor in the role of a Chicano.] What these writers have overlooked in their blind ignorance is the primary artistic esthetic: the work of a creative individual presented to an audience for a (hopefully) joyous experience in communication. But these self-righteous ones only regard these vehicles as opportunities for unleashing their age-old complaints about their offended race, nationality or religion.

If we are to cater to this kind of half-baked morality, then let our U.S. orchestras play nothing but the works of Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber and Leonard Bernstein.

A little rough in the syntax department, but I am still delighted to have put forth a sentiment that I still espouse roughly forty-five years later.

I've had to deal with the PC issue a few times in my professional life (not as many as some of my colleagues, thankfully). In every instance I've been caught off-guard by it, but at least in one case – the last of the three I'll chronicle – there was a delicious helping of vindication.

Many years ago I was conducting a student orchestra at what was essentially a summer music camp. One of the pieces I gave the students was a section from Aram Khachaturian's Gayane ballet. Now, as anyone even remotely familiar with Khachaturian's music knows, one of his most oft-used rhythms is:

1-2-3-1-2-3-1-2, 1-2-3-1-2-3-1-2

– or, put another way:

1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8

It's a kicky little rhythm that is undoubtedly a mainstay in the folk music of Khachaturian's native Armenia. It also happens to be a rhythm that one encounters in Jewish folk and popular music; you can hear it in the offerings of klezmer bands, at Jewish celebrations of coming-of-age or nuptials...and I can think of at least one usage of it in the score to Fiddler on the Roof. At one point in our rehearsals for the Khachaturian, the low strings had this rhythm in their parts but weren't emphasizing the accents quite boldly enough. By way of explanation, and speaking purely factually and with no snideness or sarcasm, I said, "Can you make it a little more Jewish?" Somehow, it worked; the young musicians got the point and the passage was played to my satisfaction. (I might also add at this point that my forbears on my father's side were Russian Jews.)

Imagine my surprise when I arrived on campus the next morning and was requested to step into the camp director's office. In the most delicate of terms, I was told that I had offended a Jewish student at the rehearsal the day before, and I was asked for a description of what had transpired. Fortunately, the explanation was all it took for the director to understand that nothing in the least bit damaging had been said, and he assured me that he'd call the student's parents forthwith and put any ill will to rest. (As I was engaged for many subsequent summers, I can only assume that I was not viewed as a threat to the students' delicate psyches.) It was gratifying in the extreme to tell this story to family and friends and get virtually the same reaction from all: "Somebody actually thought you were saying something prejudiced?!?"

A few years later, I was conducting another student orchestra, at a high school that prided itself on its progressive attitudes towards diversity. While admirable in theory, their take on the subject was somewhat different from my own; I would sum up their stance as, "We won't call attention to any ethnic, political or religious aspects of our student population, for fear of making those of other ethnicities, political beliefs or religions feel uncomfortable, marginalized, or excluded." That meant, among other things, that some students' wishes to put Christmas decorations in the cafeteria were quashed. Why not, felt I and some of my faculty colleagues, have students of other religions and ethnic backgrounds put up some of their holiday decorations, too? (Imagine what an attractive and festive display might have been the result!) No, came down the edict, better not to celebrate anything than run the risk of seeing some trends emphasized over others, etc., etc. (How do you say "Bah, humbug!" in Hebrew or Swahili?)

In an attempt to expose the orchestra to the most diverse (!) spectrum of music, I programmed works spanning from pre-Baroque to the late 20th century. Not wishing to bypass the avant-garde altogether, I scheduled a marvelous piece by Gavin Bryars entitled Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet for pre-recorded tape and ensemble (the scoring is flexible, i.e., the piece can be performed by anything from a few instruments and/or voices to a hundred-piece symphony orchestra with chorus). The pre-recorded tape consists of a sung phrase which is repeated as many times as needed (the length of each performance is variable), and at each repetition the conductor can cue in or cut off different "live" musicians, all of whose parts complement the singer on tape. It seemed a fun challenge for the young musicians, certainly outside the realm of playing something in a continuous, steady 4/4.

The voice on the tape was that of a homeless man in England, one of several persons interviewed for a documentary film on poverty, on which Bryars had been working as sound engineer. To quote Mr. Bryars:

In the course of being filmed, some people broke into drunken song – sometimes bits of opera, sometimes sentimental ballads – and one, who did not drink, sang a religious song, Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet... [The accompaniment I composed] respected the homeless man's nobility and simple faith. Although he died before he could hear what I had done with his singing, the piece remains as an eloquent, but understated testimony to his spirit and optimism.

To me, the work is primarily about music – about the timbre of the voice and Mr. Bryars' skill in coming up with so lovely an accompaniment for it. Second is the implicit program, the man's "spirit and optimism". But I do not think of this as a religious work; this is no cantata or oratorio aria, but a quietly moving testament to the composer's having been so stirred. Had the man sung a setting of a Shakespeare or Whitman verse that spoke of fortitude in the face of adversity without mentioning Jesus Christ, it would have just as stirring.

Imagine my surprise when, after describing the work at the Arts Department meeting shortly before the performance, there were some red flags about the piece – not as music, mind you, but the fear of how non-Christians might be offended by the "sacred" text. I managed to plead fairly eloquently on the piece's behalf, and eventually a compromise was reached: we could perform it, but I was to address the audience beforehand to stress that the point of the piece (and, by implication, of our performance) was its musical merits; I all but admonished the audience to ignore the words (which, I told myself with an internal grin, would then be impossible for them to do; if you tell someone, "Don't think about pink elephants!", what's the one thing about which they will surely think?). Pace, alarmists: the piece ended up being the most talked-about work we performed all year, all of the feedback positive.

But my single favorite PC story comes from my days as the Seattle Symphony's Associate Conductor. I love the orchestra, and have a treasure trove of wonderful memories associated with them. This is not to say that there wasn't occasional abrasion, as there is in any relationship of long standing.

In the fall of 1998, when Benaroya Hall was in its first few months of operation, the Symphony offered as varied a series of concerts and events as it could – classical, pop, jazz, film music – in order to attract the most diverse (there's that word again) audiences possible. One of these programs featured Gladys Knight doing an hour or so of her songs with the orchestra, for which she brought her own conductor; as frequently happened when a guest artist had a generous half-a-concert's worth of material, a "short first half" would be presented featuring the Seattle Symphony on its own. I was asked to conduct this first half, and then-Music Director Gerard Schwarz suggested "something American – upbeat, with great tunes – something like Copland's Rodeo or Bernstein's Symphonic Dances from 'West Side Story'." While pondering repertoire choices, I thought of a piece I had known from recordings since I was a small boy: Spirituals by Morton Gould. When I bounced this off of Mr. Schwarz, he said, "Perfect! Do it!" And so it was scheduled.

The third of Spirituals' five movements is effectively the work's scherzo, a charming miniature that Gould called A Little Bit of Sin. It uses a tune widely known as Short'nin' Bread, which you may not know from the title but would likely recognize due to its being used in everything from cartoons to commercials. The rehearsal for it, and the other movements, went well and the orchestra, naturally, played superbly.

Imagine my surprise when two or three members of the orchestra cornered me after the rehearsal, to express their displeasure at the Little Bit of Sin movement. "It's a slap in the face to African-Americans!" they said. "It perpetuates the stereotype of Black servants in the kitchen making pancakes!" I tried to offer some perspective: that this was a work in which a Jewish-American composer was paying homage to a culture other than his own, honoring their music with his composer's expertise – not unlike what the Australian-born Percy Grainger had done with American, Scandinavian and English folksongs in his compositions, or what Copland had done with Mexican themes in his El Salón México. My arguments fell on deaf ears; not only did they resent the programming of the piece, but their deep-seated beliefs led them to go to management to get permission to leave the stage and not play it.

Given my own beliefs, and what I thought the piece was, and what I didn't think it was, I was amazed.

The performance went on (sans the nay-players), and was enthusiastically cheered by a packed Benaroya audience.

As soon as the Gould was finished and I had taken my final bow, I snaked my way through Benaroya to get to the lobby; a friend had asked for a ticket, and we had arranged to meet at intermission if he had indeed made the concert. In the course of scanning the crowd for him, I saw, standing across the lobby, the Reverend Dr. Samuel B. McKinney (1926-2018).

For those of you unfamiliar with the name, I can only skim the surface of Dr. McKinney's extraordinary life. Dr. McKinney's accomplishments included his longtime (1958-98) pastorship at Seattle's Mount Zion Baptist Church. Dr. McKinney had originally intended to become a civil rights attorney, and even though the ministry claimed him, he remained a major figure in the civil rights movement; he marched with his old friend Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, and in Washington D.C., in the early 1960s, after having arranged for Dr. King's only Seattle visit for a series of speeches and meetings in 1961. Dr. McKinney was also an outspoken opponent of apartheid rule in South Africa; his participation in protests against it earned him at least one arrest.

About two or three years before the evening in question, I had had the pleasure of working with Dr. McKinney: he was the guest soloist at a Seattle Symphony concert in which he narrated Copland's Lincoln Portrait. In advance of his first rehearsal with the orchestra, I met him at his church to play the orchestra part on the piano so that he could practice the pacing of his recitations. His bass-baritone speaking voice, which one could only call powerful and mellifluous, was perfect for Copland's score.

That same powerful voice erupted from his throat when he caught sight of me across the lobby. "Adam!" he called, and made a gesture with his arm that as much as said, "Get over here!" (Dr. McKinney's physical presence was as formidable as his voice; he stood well over six feet, and his eyes blazed with intensity.) The phrase "moment of truth" must have crossed my mind as I approached him.

"Adam!" He beamed when I reached him, and gave me a robust embrace. "Thank you so much for playing that Morton Gould piece! I LOVED it! I heard tunes in there I hadn't heard since my grandmother sang them to me when I was a kid! Is it recorded? Can I get it on CD?" I was delighted to answer in the affirmative...and even more delighted at his response to a piece I also loved.

When I went backstage again, I called some of my friends in the orchestra over. "Will you please help me spread the word as to who just thanked us for playing the Gould?"

There's that marvelous scene in Woody Allen's Annie Hall in which a pompous blowhard is dressed down by Marshall McLuhan, the very person whose theories he has been mangling. Woody looks into the camera and says, wistfully, "Boy, if life were only like this..."

Sometimes it is.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed