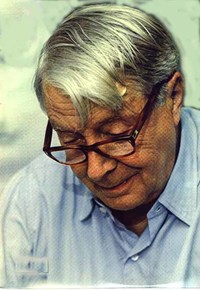

Charles Munch

Charles Munch “It’s not just for money alone that one spends a lifetime building up a business…. It’s to preserve a way of life that one knew and loved. No, I can’t see my way to selling out to the new vested interests, Mr. Jorkin. I’ll have to be loyal to the old ways and die out with them if needs must.”

-- Mr. Fezziwig, from the 1951 film adaptation of Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol", explaining his traditional beliefs to colleague Mr. Jorkin who is urging him to "sell out while the going’s good"

"In some settings (notably Tanglewood for the Boston Symphony) video screens provide a frontal view of the conductor as well as closeups of musicians. This greatly enhances the audiences' enjoyment and understanding of the performance. Only the fuddy-duddyism that also dictates penguin suits and other anachronisms prevents this from becoming a standard... If our classical orchestras decline to adapt to the modern world, they will simply fade away."

-- from an April 6, 2012 entry to another's blog dealing with music, conductors and orchestras

I'm with Fezziwig.

It's not stubbornness; it's not affectation; it has nothing to do with a desire to be seen in a particular light. It has everything to do with a profound love and respect for musical traditions, and my refusal to give way to an entirely wrongheaded way of thinking that has insidiously crept into the presentation of classical music over the last several decades. This odious philosophy can be summed up as follows: "Audiences are changing, and concerts have to change accordingly, too."

Unfortunately, and dangerously, many of the purveyors of this viewpoint occupy positions of considerable power in the music world: executives in broadcast media and the recording industry, administrators of performance groups, and, to my shame, conductors, instrumentalists and singers who either should know better or have simply "caved". In the arena I primarliy occupy – that of the symphony orchestra – I have watched in everything from astonishment to fury as standards have slipped down the drain, into the septic tank known as The Lowest Common Denominator. This is reflected both in the music performed and the way in which said music is promulgated.

Take, for example, the realm of children's or educational concerts. Did anyone ever do these better than Leonard Bernstein, whose Young People's Concerts can still be savored for their explicational excellence and the quality of the music chosen to disseminate? Bernstein didn't pander, nor did he necessarily hew to the most famous or "accessible" of music to examine: Mahler, Bartók, Hindemith, Revueltas, Copland and Stravinsky (a complete performance of Petrouchka!) shared the bills with Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. In his demeanor, too, Bernstein refused to speak of music as so much pablum; I fondly remember his "Humor in Music" lecture that made copious use of the word "incongruous" when describing deliberate wrong notes, funny orchestral colors, and other musical hijinks. Here is Bernstein himself, justifiably satisfied, speaking to his accomplishments:

"When you know that you're reaching children without compromise or the assistance of acrobats, marching bands, slides, and movies, but that you are getting them with hard talk, a piano, and an orchestra, it gives you a gratification that is enormous."

Cut to roughly three decades later, when an unnamed conductor (he's currently at his laptop) was himself officiating over children's concerts, as both writer/commentator and conductor. After several of these were performed with a professional symphony orchestra, the orchestra's education director informed him that, due to what she perceived as too highfalutin an approach in his scripts, she wanted more editorial input (translation: co-authorship). When the conductor asked in genuine surprise for an example, he was told (and I quote): "You use words like 'melody'. That's too big a word for kids; say 'tune'."

How I wish the conductor had called her on her incongruousness.

Their relationship slowly disintegrated over the next few seasons as the conductor was given more and more questionable mandates – among them, to limit all but the rarest musical selections to those that were fast, loud and short. His question about how children – supposedly in attendance to increase their knowledge about music and its perception – were to learn how to absorb, among other things, a slow and/or quiet and/or lengthy (i.e., more than five minutes) piece, was essentially shrugged off; "they'll just have to do that somewhere else" was the implication. Eventually, when the scripts devolved to the point where the conductor was embarrassed to have their words coming out of his mouth, he requested that his role be limited to preparing and conducting the music, with a separate narrator engaged to recite the verbal material. Happily, the request was granted.

The whole subject has a unsettling similarity to what has happened to school textbooks. In an excellent 1997 article, "A Dumbed-Down Textbook is 'A Textbook for All Students'", William J. Bennetta makes the following observations following some disquieting testimony by himself and others in the book publishing milieu:

"Major schoolbook companies are making their books dumber than ever, because they perceive that there is a big, ready market for such products. The market is provided by schools where 'education' consists chiefly of submerging students in feel-good pastimes, furnishing students with easy successes, and ensuring that even the laziest and the worst-prepared students will seem to be doing well. [...] In its heaviest and most pernicious form, the dumbing down of high-school books comprises four interlocking processes. The first is the elimination or dilapidation of concepts that may require a student to expend mental effort: such concepts are excised entirely, or they are reduced to little heaps of factoids. Next comes the process that [James] Michener saw sixty years ago* and that is still going on – the reduction and impoverishment of vocabulary. Then comes the ostensible simplification of style, effected partly through the suppression of compound or complex sentences. This process often requires that logical connections be destroyed for the sake of ensuring that sentences will be simple and short. Finally comes the replacement of written material by pictures – pictures which, as often as not, are mere decorations."

*Author James Michener is quoted earlier in the article in reference to his erstwhile work as a textbook editor for Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Do you, as I do, detect more than a slight parallel between the requests for "tune" over "melody" and the eschewing of any slow or soft music on the one hand, and "dilapidation of concepts", "impoverishment of vocabulary" and "simplification of style" on the other?

Alas, my concerns are not limited to the sphere of concerts for the young; the misguided and shortsighted have gotten their claws into the world of regular symphony concerts as well. I am not speaking here of "pops" programs, or concert-hall presentations of movies wherein an orchestra plays the score live, or special programs explicitly and honestly packaged as "events" that involve symphonic music. I am writing of the sorts of time-honored concerts that are becoming a potentially endangered species: experiences that are built on the idea of listening intently and undistractedly to well-rehearsed and inspired performances, what the great conductor Charles Munch called "a true musical communion".

Munch, idealistic in the extreme (and bless him for that), believed that "the public comes to concerts to hear good performances of beautiful music just as it goes to museums to look at beautiful pictures or statues. It comes to be enriched, instructed, fortified." I wonder what he would think of some contemporary practices which have been adopted in the name of catering to the putative needs of modern audiences: the dutiful trotting-out of the same repertoire staples every two or three seasons; slide-shows or videos accompanying such already-mega-pictorial music as Pictures at an Exhibition or The Planets; conductors and/or soloists indulging in cutesy-poo, drone-on monologues before one (in some cases, every) piece on every program; announcements from the stage or over the P.A. system to apprise audiences of sports scores. To invoke Maestro Munch again, he referred to his work as "a priesthood, not a profession." I couldn't agree more strongly, and I'm damned if I would resort to travesties in the concert-hall any more than I would belittle God or the teachings of Jesus Christ were I a clergyman: "In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. Oh, and the Mets just won!"

At the concerts over which I preside, I will do my part to enrich, instruct and fortify, via the best performances and most intelligent and varied programs I can present, irrespective of how incongruous my efforts may seem to some in the modern world. For centuries, Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven have had plenty to say and offer to anyone who would really listen, and I for one don't believe that those of us in the present age – awash though we may be in instantaneous communications, lousier-than-ever television shows, and apps for everything – are any less capable of receiving the music's messages. If I may dip once more into the fount of wisdom of the legendarily gentle and humble Mr. Munch: "The music, the interpreter, and the public form a tri-partite entity in which each factor is indispensible to the other."

An unseasonal tip of the wassail bowl, then, to all Fezziwigs – and the Munches and Bennettas of the world – for reminding us, in word and deed, about standards and priorities. May they continue to edify, enlighten and embolden us.

-- Mr. Fezziwig, from the 1951 film adaptation of Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol", explaining his traditional beliefs to colleague Mr. Jorkin who is urging him to "sell out while the going’s good"

"In some settings (notably Tanglewood for the Boston Symphony) video screens provide a frontal view of the conductor as well as closeups of musicians. This greatly enhances the audiences' enjoyment and understanding of the performance. Only the fuddy-duddyism that also dictates penguin suits and other anachronisms prevents this from becoming a standard... If our classical orchestras decline to adapt to the modern world, they will simply fade away."

-- from an April 6, 2012 entry to another's blog dealing with music, conductors and orchestras

I'm with Fezziwig.

It's not stubbornness; it's not affectation; it has nothing to do with a desire to be seen in a particular light. It has everything to do with a profound love and respect for musical traditions, and my refusal to give way to an entirely wrongheaded way of thinking that has insidiously crept into the presentation of classical music over the last several decades. This odious philosophy can be summed up as follows: "Audiences are changing, and concerts have to change accordingly, too."

Unfortunately, and dangerously, many of the purveyors of this viewpoint occupy positions of considerable power in the music world: executives in broadcast media and the recording industry, administrators of performance groups, and, to my shame, conductors, instrumentalists and singers who either should know better or have simply "caved". In the arena I primarliy occupy – that of the symphony orchestra – I have watched in everything from astonishment to fury as standards have slipped down the drain, into the septic tank known as The Lowest Common Denominator. This is reflected both in the music performed and the way in which said music is promulgated.

Take, for example, the realm of children's or educational concerts. Did anyone ever do these better than Leonard Bernstein, whose Young People's Concerts can still be savored for their explicational excellence and the quality of the music chosen to disseminate? Bernstein didn't pander, nor did he necessarily hew to the most famous or "accessible" of music to examine: Mahler, Bartók, Hindemith, Revueltas, Copland and Stravinsky (a complete performance of Petrouchka!) shared the bills with Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. In his demeanor, too, Bernstein refused to speak of music as so much pablum; I fondly remember his "Humor in Music" lecture that made copious use of the word "incongruous" when describing deliberate wrong notes, funny orchestral colors, and other musical hijinks. Here is Bernstein himself, justifiably satisfied, speaking to his accomplishments:

"When you know that you're reaching children without compromise or the assistance of acrobats, marching bands, slides, and movies, but that you are getting them with hard talk, a piano, and an orchestra, it gives you a gratification that is enormous."

Cut to roughly three decades later, when an unnamed conductor (he's currently at his laptop) was himself officiating over children's concerts, as both writer/commentator and conductor. After several of these were performed with a professional symphony orchestra, the orchestra's education director informed him that, due to what she perceived as too highfalutin an approach in his scripts, she wanted more editorial input (translation: co-authorship). When the conductor asked in genuine surprise for an example, he was told (and I quote): "You use words like 'melody'. That's too big a word for kids; say 'tune'."

How I wish the conductor had called her on her incongruousness.

Their relationship slowly disintegrated over the next few seasons as the conductor was given more and more questionable mandates – among them, to limit all but the rarest musical selections to those that were fast, loud and short. His question about how children – supposedly in attendance to increase their knowledge about music and its perception – were to learn how to absorb, among other things, a slow and/or quiet and/or lengthy (i.e., more than five minutes) piece, was essentially shrugged off; "they'll just have to do that somewhere else" was the implication. Eventually, when the scripts devolved to the point where the conductor was embarrassed to have their words coming out of his mouth, he requested that his role be limited to preparing and conducting the music, with a separate narrator engaged to recite the verbal material. Happily, the request was granted.

The whole subject has a unsettling similarity to what has happened to school textbooks. In an excellent 1997 article, "A Dumbed-Down Textbook is 'A Textbook for All Students'", William J. Bennetta makes the following observations following some disquieting testimony by himself and others in the book publishing milieu:

"Major schoolbook companies are making their books dumber than ever, because they perceive that there is a big, ready market for such products. The market is provided by schools where 'education' consists chiefly of submerging students in feel-good pastimes, furnishing students with easy successes, and ensuring that even the laziest and the worst-prepared students will seem to be doing well. [...] In its heaviest and most pernicious form, the dumbing down of high-school books comprises four interlocking processes. The first is the elimination or dilapidation of concepts that may require a student to expend mental effort: such concepts are excised entirely, or they are reduced to little heaps of factoids. Next comes the process that [James] Michener saw sixty years ago* and that is still going on – the reduction and impoverishment of vocabulary. Then comes the ostensible simplification of style, effected partly through the suppression of compound or complex sentences. This process often requires that logical connections be destroyed for the sake of ensuring that sentences will be simple and short. Finally comes the replacement of written material by pictures – pictures which, as often as not, are mere decorations."

*Author James Michener is quoted earlier in the article in reference to his erstwhile work as a textbook editor for Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Do you, as I do, detect more than a slight parallel between the requests for "tune" over "melody" and the eschewing of any slow or soft music on the one hand, and "dilapidation of concepts", "impoverishment of vocabulary" and "simplification of style" on the other?

Alas, my concerns are not limited to the sphere of concerts for the young; the misguided and shortsighted have gotten their claws into the world of regular symphony concerts as well. I am not speaking here of "pops" programs, or concert-hall presentations of movies wherein an orchestra plays the score live, or special programs explicitly and honestly packaged as "events" that involve symphonic music. I am writing of the sorts of time-honored concerts that are becoming a potentially endangered species: experiences that are built on the idea of listening intently and undistractedly to well-rehearsed and inspired performances, what the great conductor Charles Munch called "a true musical communion".

Munch, idealistic in the extreme (and bless him for that), believed that "the public comes to concerts to hear good performances of beautiful music just as it goes to museums to look at beautiful pictures or statues. It comes to be enriched, instructed, fortified." I wonder what he would think of some contemporary practices which have been adopted in the name of catering to the putative needs of modern audiences: the dutiful trotting-out of the same repertoire staples every two or three seasons; slide-shows or videos accompanying such already-mega-pictorial music as Pictures at an Exhibition or The Planets; conductors and/or soloists indulging in cutesy-poo, drone-on monologues before one (in some cases, every) piece on every program; announcements from the stage or over the P.A. system to apprise audiences of sports scores. To invoke Maestro Munch again, he referred to his work as "a priesthood, not a profession." I couldn't agree more strongly, and I'm damned if I would resort to travesties in the concert-hall any more than I would belittle God or the teachings of Jesus Christ were I a clergyman: "In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. Oh, and the Mets just won!"

At the concerts over which I preside, I will do my part to enrich, instruct and fortify, via the best performances and most intelligent and varied programs I can present, irrespective of how incongruous my efforts may seem to some in the modern world. For centuries, Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven have had plenty to say and offer to anyone who would really listen, and I for one don't believe that those of us in the present age – awash though we may be in instantaneous communications, lousier-than-ever television shows, and apps for everything – are any less capable of receiving the music's messages. If I may dip once more into the fount of wisdom of the legendarily gentle and humble Mr. Munch: "The music, the interpreter, and the public form a tri-partite entity in which each factor is indispensible to the other."

An unseasonal tip of the wassail bowl, then, to all Fezziwigs – and the Munches and Bennettas of the world – for reminding us, in word and deed, about standards and priorities. May they continue to edify, enlighten and embolden us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed